My life of crime began – and ended – early. Very early.

I was five years old, hogging the backseat on a family car trip across Texas, too little to know where we were coming from or going to. I do recall our stopping in one city long enough to enjoy the hospitality of some old friends of my parents, who’d invited us to their home for dinner.

I remember that much, because as we stepped through the front door and into their hall, my eyes fell on the most magnificent sight I’d ever seen: a big crystal bowl of candy, set smack in the middle of a tall table at the center of the room.

Our hostess, catching the wondering glow in my eye, laughed and assured me I could have “as much of that candy as you want.” My mother, seeing a gleam of gluttony, corrected her friend’s kind invitation.

“One piece,” she told me, firmly. Then they walked, chattering happily, from the room.

That left me with naught but my beleaguered conscience for company. “One piece,” the angel on my shoulder reminded me. “As much as you want,” the devil on my other scapula corrected him. “And it’s her house!” he added, for emphasis.

My conscience found that last argument, in particular, not just convincing, but compelling. I found a chair, scrambled up to the table, lifted the jar lid, grabbed a fistful of sweets, and stuffed them deep into my pocket. A moment later, the lid was back, the chair was returned to its corner … and the Great Candy Caper had been accomplished with no one the wiser.

The happy evening ended, the fond goodbyes were said, and I scrambled onto the backseat, savoring the feel, deep in my pocket, of all those plastic wrappers between my fingers. Although … it concerned me that there seemed to be one or two fewer candies there, now, than I’d been feeling in all my other fingering expeditions throughout the night.

Suddenly, and simultaneously, I felt two odd sensations: one, a tiny hole, at the bottom of the candy pocket. And two, something tickling my leg as it rolled down toward my ankle, out from under my pants cuff, and onto the floorboard below.

My young boy’s mind was just completing the math on that one-two when my mother, unaccountably, elected to slide onto the seat beside me. What was she doing back here?

Another something slid down leg, as I slid across the seat to make room for Mom. Then: we both heard something crunch beneath the sole of her shoe. “What was that?” she asked.

“I don’t know,” I said, looking fervently out the window beside me. I squirmed, as she looked down toward our feet. Another something trickled along my leg.

She bent down and came up with one of my candies. “Where’d this come from?” she asked.

A gifted Boy Scout could not have untied the knots in my tongue. “I … um .. it … I … she ….” The jig was utterly up. And someone was about to be wiser.

The charges soon presented were not without merit: disobedience of parents, grand theft candy, secrecy with intent to defraud, and misdemeanor smuggling. Only my inability to work the door lock prevented “flight to avoid prosecution” from joining the list.

The verdict was a foregone conclusion. The sentence was pronounced as we walked back into our motel room: I was to call our hostess and apologize for taking so much of her candy.

I would gladly have accepted the death penalty as an alternative. The unspeakable horror of that nice, smiling lady looking upon me, forevermore, as a wicked child and hardened felon chilled my soul to the bone.

But my parents were adamant. The call was made. If ‘d listened, I might have heard, over my thundering heart, the muffled sounds of mirth and mercy in the voice of the kind woman on the other end of the line. But I wasn’t listening. I was learning.

There’s a price to be paid for stealing. And I didn’t want to ever have to pay that price again.

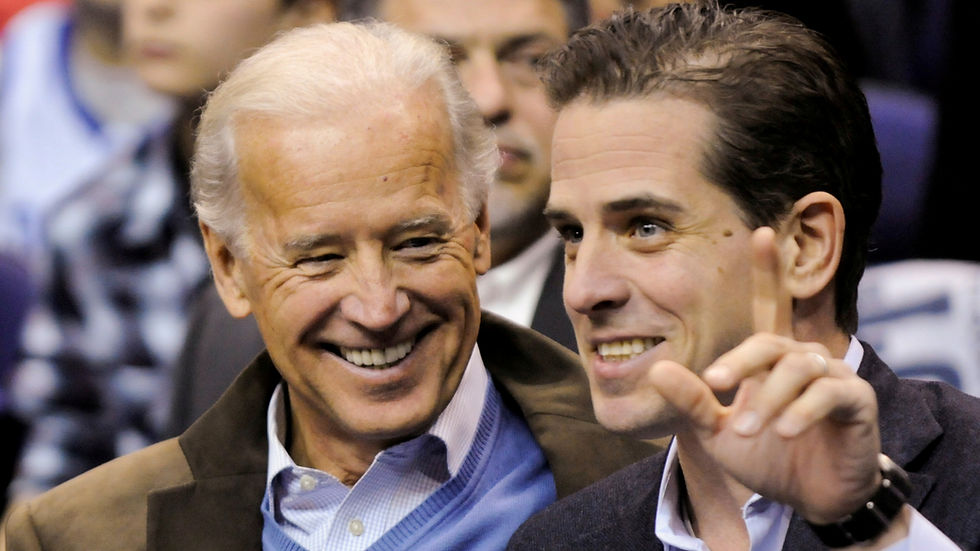

I’m guessing Hunter Biden never had a similar experience. Going off my observations of his father, these last two or three decades, I’d bet if a nice lady had encouraged young Hunter to “take as much candy as you want,” his dad would have laughed and said, “Go for it, boy.” And not a piece would’ve been left as they drove away.

Or, that if Hunter had indulged his sweet tooth without such encouragement, but with the same kind of hole in his pocket, his dad would have laughed at that, too – tousled his son’s hair, and taken one or two of the candies for himself.

One thing ‘m very sure of: Hunter never would have been required to make that phone call. Holding people responsible is not something Bidens do. Not their staff, not their generals, not their cabinet members or allies. And certainly not – especially not – their children.

Which is why the rather remarkably extensive pardon the president gave his son last week outraged a lot of people, incensed a lot of people, provoked a lot of people … but didn’t really surprise anyone. Holding Hunter accountable – for crimes great or small – just isn’t, and never has been, on the president’s (admittedly minimal) moral radar.

Bidens, we all know, look out for Bidens. Mostly, by giving each other whatever they want.

Some may chalk that up to a father’s love, of one kind or another. Maybe for Hunter himself, maybe as a proxy for another son, lost to cancer years ago and clearly never far from the president’s increasingly slippery mind.

But the president’s affections, however ardent, are muddled by a tangible contempt for the law. “I’m sorry, but he’s my son,” is an explanation many might grumble at, but few could refute. The president feels what he feels, and is in a position to indulge those emotions.

Yet he couldn’t bring himself to just say that, and have done with it. He opted to cloak his indulgence in a litany of excuses that not even his political allies can accept with straight face. In the end, everything clearly came down to: “protecting my son is more important than upholding the law.” Self-indulgence trumps personal integrity.

Politics aside, it makes for a sad contrast with the character of the God the president professes to embrace, and whose teachings he has pledged to follow. Indeed, it would be hard to find a course of action more directly the opposite of the one God Himself pursued, in allowing His own, innocent Son to be sacrificed for the sins of others.

God, Scripture tells us, doesn’t look at His children and say, “You rascals … went and did the wrong thing again, didn’t you? Tell you what: let’s just pretend it never happened. I love you, you scamps.” God speaks, instead, the simple, unwavering truth. “There’s a price to be paid. Always. And you can’t pay it. So My Son's going to pay it for you.”

The president, on the other hand, seems convinced that Hunter should never be required to answer for his own sins – much less bear any burden for others.

Which means, whatever love the president feels for his surviving son … it's never been the kind that would help him to be a better person. Encourage him to make sacrifices for those around him. Or to understand the heart of God. And what is a father for, if not to teach his son these things?

“My son, do not despise the Lord's discipline, or be weary of His reproof, for the Lord reproves him whom He loves, as a father the son in whom he delights.”

I’m sure the president felt he was doing the right thing, making the call he did on Hunter’s behalf. But, oh, if only – somewhere, early on – he’d required Hunter to make a call for himself.

コメント