Sights For Sore Eyes

- writingingreen

- Jan 20

- 4 min read

“Que sera, sera

Whatever will be, will be

The future’s not ours to see

Que sera, sera.”

I don’t see as well as I used to. And I didn’t used to see all that well.

My teacher thought it strange that this little boy on the second row couldn’t read a blackboard. My mom wondered why her young son couldn’t find things she asked me to hand her, even when they were right in front of me. My dad couldn’t figure out why his future Golden Glover was so terrible at fielding a baseball.

Even out in left field, I could hear the crack of the bat, clear enough … I just couldn’t see the ball until it suddenly appeared, a foot away from my face, hurtling in hard and fast. My bad eyes scored a lot of runs for the other team.

The thing is, when you’re born with bad vision, you don’t know that it’s bad vision. You just assume the whole world sees the same fuzzy, double images you do. If anything, you’re impressed with how well others seem to function amid the fog: how exactly do those other kids read what’s scribbled on the blackboard, or sense that invisible ball, plunging down from above?

My crisis was finally resolved the night my dad took me to my first professional basketball game; I kept pestering him about who was ahead. “Read the scoreboard,” he said, pointing to the Jumbotron. “What scoreboard?” I asked, looking up at that big blur of lights hanging down from the rafters. The next day, I met my first optometrist.

After that, it was just the same lifelong routine most cornea-compromised people deal with: picking out new frames, adjusting prescriptions, figuring out where you left your glasses when you walked out of the room, trying not to sit on them or step on them or otherwise make a spectacle of yourself.

Then, a few years ago, the “floaters” appeared: dark spots that keep drifting across my line of vision. I found myself swatting at elusive bugs or wondering how these slugs had wormed their way onto my pupils. “It’s an age thing,” the eye doc said. But when the drifting microscopic debris began crowding everything else off my viewing screen, she suggested surgery.

The operation, she said, would involve draining all of the fluid from my eyes, then substituting an imitation liquid to hold me for a few days, until my body could replenish my ojos with some new, “home-grown,” floater-free stuff. Not a big deal, she assured me. “Just think of it as open-heart surgery for your eyes.” Uh-huh.

I opted for the optimum optical solution, the operations went smoothly, and my floaters are no more. But the procedures played havoc with my old eyeglass prescription, and now … ‘m eight years old all over again, groping my way through a blurry world while I wait for the new lenses to be readied.

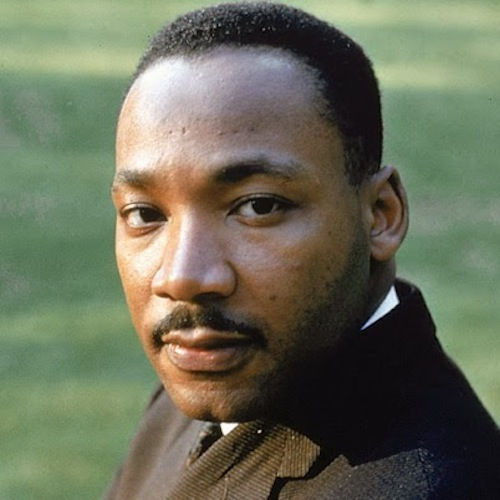

Which brings me to Martin Luther King, Jr.’s birthday, today, and to something he said, during his last night on earth. The man who had a dream had lived to see a great deal of that dream come true. His world had changed, with remarkable speed and at great cost, in those long days and years since he first stepped up to suggest, with commanding eloquence, that his world really should.

But he was older, and seemed tired, that last night in Memphis. The once-clear vision had become increasingly clouded by changing political realities, a war, a new generation looking for more aggressive leaders. Threats continued to be made against his life, and his own mortality loomed large in his mind.

“I don't know what will happen now,” he told a restless crowd of striking garbage workers. “We've got some difficult days ahead. But it doesn't matter with me now. Because I've been to the mountaintop. And I don't mind.

“Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I'm not concerned about that now. I just want to do God's will. And He's allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I've looked over. And I've seen the Promised Land.

“I may not get there with you," he said. "But I want you to know, tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land. So I'm happy ... I'm not worried about anything. I'm not fearing any man. ‘Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.’”

Twenty-four hours later, he was dead.

The lyrics he quoted were, of course, from The Battle Hymn of the Republic, which was beautifully played and sung this morning, at President Trump’s second inauguration. Mr. Trump, who has lived a long and crowded life, spoke to his own dream: a vision of a new “golden age” for America. But his vision, too, is plagued by floaters – entrenched opponents, legalities and logistics, so many events no one can see coming.

Hopes are high, and the dream is 20/20. But 24 hours / days / years from now? The future is a blur.

I suppose that’s true for all of us. Some are focused on clear dreams and concrete plans. We are moving, as best we can, toward the vision. We just “want to do the Lord’s will.”

But some of us wonder, maybe, if we’ve been to the mountaintop – if what we’ve already been blessed to see is, really, the best we will see, this side of glory. We look inside ourselves, clear-eyed, to see if we’re content, and happy.

Those assessments are sometimes a little blurry. While mortality, each day, becomes a little more clear.

Our Father, I suspect, has surprises in store for all of us. Possibilities, still fuzzy, on the far-off horizon. “Eye has not seen, nor ear heard, nor have entered into the heart of man," the Bible says, "the things which God has prepared for those who love Him.”

May our love be focused. And our ears attentive to the crack of distant bats.

Open our eyes, Lord, that we may see.

Great perspective. Thank you for your analysis.